Even before Democrats pressured then-President Joe Biden to drop out of the 2024 presidential race over concerns about his age, voters had been calling for generational change in Washington. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that 82% of Republicans and 76% of Democrats back an age limit for federal elected officials.

The Silent Generation’s ranks have dwindled from 39 members in 2021 to 24 in 2025, as Gen X and millennial politicians replace older lawmakers. Still, at least 13 have indicated plans to run for re-election, creating the possibility of this generation’s holding on to seats into the next decade and reigniting a debate about how long is too long to serve in office.

“The average age of a Congress member is when most people are thinking about retiring. And we’ve seen so many examples of people who just wear out their welcome and stay in past their sell-by date,” said Nick Tomboulides, CEO of U.S. Term Limits, a nonpartisan group that backs a constitutional amendment to limit congressional terms.

“We don’t think senility is really the problem. We think incumbency is the problem, and senility is the symptom,” he added. “Because when these incumbents can run effectively unopposed or under-opposed for so long, they really have no incentive to leave.”

Some Silent Generation members in Congress, though, told NBC News they still love what they do and that their seniority and experience helps them effectively deliver results for their constituents.

Power and influence

Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman Jim Risch, R-Idaho, who is running for re-election this fall, will be 83 on Election Day and would be 89 years old at the end of that new six-year term. But he said he’s still enjoying the job, and his powerful position as chairman has put him at the center of the debate over Venezuela, Greenland and other global flash points — issues over which he regularly spars with reporters.

“I don’t know what the Silent Generation is. I didn’t know that we were silent,” Risch joked in the Capitol. “You got to like the job, and you got to have enough time to spend with your family, and you got to have your health, and if you’ve got your health and you’re doing what you want to do, why not?”

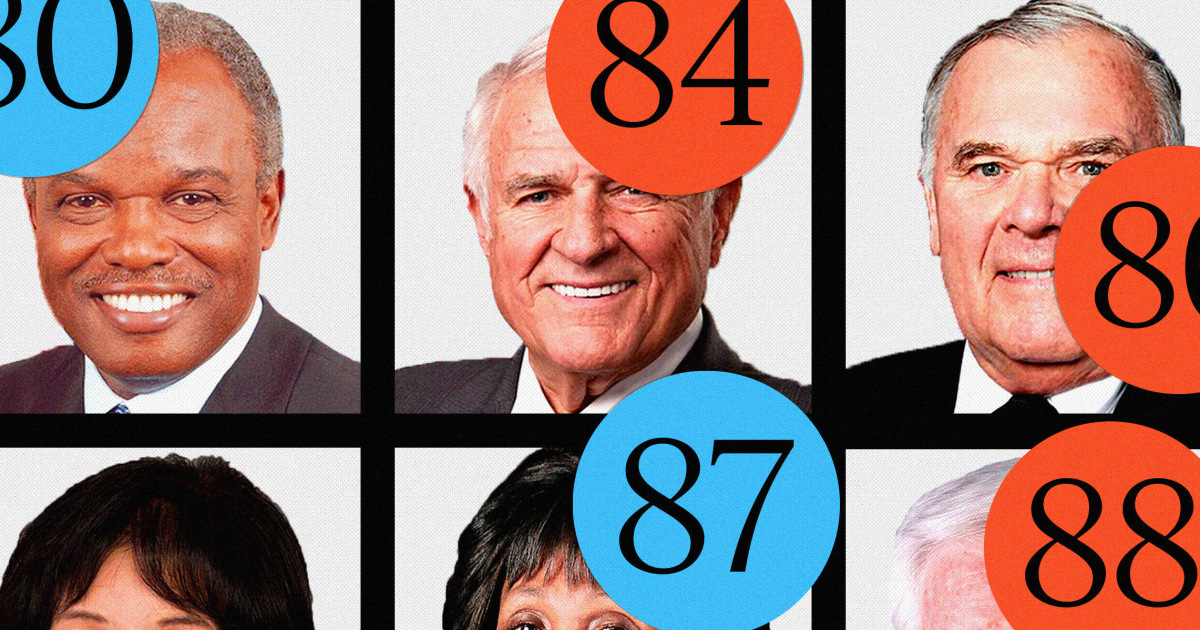

In the House, Maxine Waters of California, the top Democrat on the powerful Financial Services Committee, who has served since 1991, will be 88 on Election Day; Democrat Eleanor Holmes Norton, the longtime delegate from Washington, D.C., who faces a tough primary challenge, will be 89; David Scott, D-Ga., the former chairman of the Agriculture Committee, who is also in a competitive primary, will be 81; and Doris Matsui of California, the top Democrat on a key Energy and Commerce subcommittee, will be 82.

Across the aisle, Rules Committee Chairwoman Virginia Foxx, R-N.C., who has served in the House since 2005, will be 83 on Election Day; Rep. Hal Rogers, R-Ky., the dean of the House and a former Appropriations Committee chairman who continues to play a key role on that panel, will be 88; Rep. John Carter, R-Texas, another top appropriator, will be 84; and Rep. Jim Baird, R-Ind., who was hospitalized after a car accident last week, will be 81.

All are running for new two-year terms in the House in November.

Sporting a neck brace and a black eye, Baird, a decorated Vietnam war veteran, told NBC News he’s running because “I love my country. I want my grandkids and my kids to have the same opportunity as I had.”

Many of those lawmakers have secured positions that wield enormous power and influence on Capitol Hill through seniority.

Along with the title of “chairman” or “ranking member” of a top committee comes control over funding and legislative agendas, extra office space, committee rooms and staff rosters that, in some cases, reach into the dozens.

Waters will be Financial Services Committee chairwoman again if Democrats take back the House in November. “My work is not finished, and I don’t know if it will ever be finished,” she told NBC News.

Carter, a soft-spoken former county judge affectionately known on the Hill as “Judge,” said that as chairman of the Appropriations Subcommittee for Military Construction and Veterans Affairs, he can advocate for military service members, veterans and his central Texas district, which is home to Fort Hood. If he relinquished his seat, a new member wouldn’t be likely to win a seat on his influential committee, which controls the government’s purse strings, he argued.

“It’s not about power,” Carter, who has served since 2003, told NBC News. “I am a voice for the Army.”

Said Rogers of Kentucky, who was first elected to the House in the 1980 Reagan Revolution: “As long as I can be helpful to the constituents I represent, I’ll keep working.”

Rep. John Garamendi, D-Calif., 80, was state insurance commissioner and lieutenant governor and Bill Clinton’s deputy secretary of the interior. He has served in the House since 2009.

“I’ve got many, many years of experience — state and federal — and to be able to apply it here on these challenging issues, and every year is a challenging issue, I just love to work on the policy,” said Garamendi, who will become chairman of the Armed Services subcommittee on readiness if Democrats win the House.

There has been a Matsui in Congress since Jimmy Carter was president. In 2005, Doris Matsui succeeded her late husband, Bob, who was first elected in 1978. Matsui, a Democrat from Sacramento, said in a statement she’s “still delivering results for my community.”

“At a moment when Donald Trump is attacking our people and democratic values, I’m more committed than ever to fighting back and advancing our communities’ interests: bringing resources home, lowering costs, and leading on health care, the environment, and technology,” she said.

End of the Pelosi and McConnell era

To be sure, at least seven of the old bulls in Congress are heading for the exits.

They are Pelosi, D-Calif., 85, who arrived in Congress in 1987 and made history as the first and only female speaker of the House; Hoyer, D-Md., 86, who has served since 1981; McConnell, 83, a Republican, who set records as the longest-serving senator from Kentucky and the longest-serving Senate leader of either party; Senate Minority Leader Dick Durbin, D-Ill., 81, who was first elected to the House in 1981 and the Senate in 1996; and Reps. Danny Davis, D-Ill., 84; Jan Schakowsky, D-Ill., 81; and Bonnie Watson Coleman, D-N.J., 80.

Former House Majority Whip James Clyburn, D-S.C., 85, who served alongside Pelosi and Hoyer in leadership for roughly two decades, has said he’ll decide about his future in the coming weeks.

Davis, who was first elected to Congress three decades ago, said it was time to leave, given his age and his health.

“As of this year, I will have spent 46 years as an elected official. I spent 11 years on the Chicago City Council. I spent six years on the county board, and I will have done 30 years here,” Davis, holding a walking cane, told NBC News in the Capitol. “And my health is what it is. I still have some health challenges, and there is always talk of ‘it’s time for one generation to move on.’ I have had a wonderful time as an elected person and as an engaged person.”

In the Senate, where terms last for six years rather than two, the reality of aging is a bigger factor.

Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, who is president pro tempore, third in line to the presidency, by virtue of being the longest-serving senator, hasn’t said whether he will seek a ninth six-year term in 2028, when he would turn 95. He was first elected to the House in 1974 and to the Senate in 1980.

Speaking to reporters last summer, Grassley left open the possibility of running again, though he acknowledged he’d need to weigh the same factors he has in recent elections, including “whether or not I can do the job.”

Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., the liberal icon who caucuses with Democrats, isn’t up for re-election until 2030, when he would turn 89. After he won re-election in 2024, he said this term was likely to be his last. Sanders, the top Democrat on the Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee, was first elected to the House in 1980 and to the Senate in 2006.

Asked last week whether this, in fact, would be his last term, Sanders replied: “You think that’s the issue of the day?”

And Sen. Angus King of Maine, an independent who also caucuses with Democrats, is also up for re-election in 2030, when he would turn 86. When NBC News asked King whether this is his last term, Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H., 78, who announced her own retirement last year, walked by and interjected with a smile: “Don’t answer that.”

“Well, I’ve got five more years,” said King, who won his third Senate term in 2024. “No, I’m not thinking about that. I’ve got plenty on my mind right now.”

Cleaver, Kansas City’s first Black mayor, who was later elected to Congress in 2004, said he’d contemplated announcing his retirement this cycle. Then, Missouri got pulled into the national mid-decade redistricting battle, and Missouri Republicans redrew his district to make it more Republican. Cleaver decided to run again to fight the GOP move.

Cleaver said seeking a 12th term has helped redistricting opponents collect signatures for a referendum to stop the new map.

“There would be no way for me to retire now, and the reason is the effort to eliminate the seat caused me and many of my supporters to say, ‘Not now,’” he said.

Asked what keeps him coming back, Cleaver deadpanned: “Mental illness.”