WASHINGTON — He has been in exile for 47 years, a crown prince without a country. But Reza Pahlavi says his moment has arrived and insists his fellow Iranians will soon topple the clerical regime that ousted his father.

“They are demanding a credible new path forward,” Pahlavi said at a news conference in Washington last week. “They have called for me to lead.”

Although sometimes dismissed as politically irrelevant over the years, Pahlavi has gained new prominence in recent weeks as Iranian protesters chanted his name and reposted his social media appeals. But it remains unclear if Pahlavi has the political organizing skills and enough support inside Iran — or in the White House — to help topple the regime and steer the country to a democratic future.

Large-scale street protests that swept the country starting in late December have subsided after Iranian security forces opened fire on unarmed demonstrators, killing thousands, according to human rights groups.

President Donald Trump has referred to Pahlavi as a “nice guy” but questioned whether the son of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi could be a future leader. “He seems very nice, but I don’t know how he’d play within his own country,” Trump told Reuters earlier this month.

In appearances on Fox News and elsewhere, Pahlavi has praised Trump for promising to come to the aid of protesters and said he believes the president is “a man of his word.”

In Trump’s first term, senior officials overseeing Iran policy stayed in close contact with Pahlavi and other opposition activists. But in Trump’s second term, Pahlavi has struggled to get an inside track with the president’s advisers, though he says he is in communication with the administration. The president’s top envoy, Steve Witkoff, has held talks with Pahlavi.

Although Trump has threatened to intervene if Iran executes protesters, the Iranian government presents a more complicated challenge for any possible regime change operation than Venezuela, where the administration earlier this month captured the president there, Nicolás Maduro.

Unlike Venezuela, Iran has a more fractured opposition, and so far there are no signs of major defections inside the regime’s security forces, according to Western officials.

On Thursday, Trump left open the possibility that he might order military action against the regime, saying a U.S. “armada” was headed to the region. “We have a massive fleet heading in that direction, and maybe we won’t have to use it. We’ll see,” Trump told reporters aboard Air Force One.

A White House spokesperson pointed to Trump’s comments about Pahlavi when asked for comment.

In public opinion surveys in Iran over the past three years, Pahlavi receives stronger support than any other opposition figure by a wide margin, with about 30% of Iranians strongly backing him, according to polling overseen by Ammar Maleki of the University of Tilburg in the Netherlands. But about 30% oppose him and another third are undecided.

“He does have support. He can mobilize people,” said Andrew Ghalili, policy director at the National Union for Democracy in Iran, a nonprofit that has worked closely with Pahlavi.

Pahlavi’s higher profile is partly due to the Iranian regime’s systematic repression of critics and dissidents, almost all of whom are behind bars, said Ali Vaez of the International Crisis Group think tank.

“His stock has certainly gone up recently,” Vaez said. “The Iranian regime has eliminated any competition,” he added, “because every Iranian dissident who could potentially mobilize masses inside the country is sitting in a prison.”

Pahlavi’s famous late father helps fuel his appeal among some Iranians, as there is a degree of nostalgia for a time when the country was not an international pariah and clerics did not restrict social freedoms. But the shah’s reign divides Iranians, who recall the royal court’s lavish lifestyle and repression by a vast secret police force.

Elliott Abrams, who was Trump’s special envoy to Iran and also to Venezuela in Trump’s first term, said Pahlavi’s popularity reflects the deep-seated outrage Iranians harbor against the government in Tehran.

“Pahlavi’s new prominence is a natural product of hatred of the regime by the Iranian people. To chant his name or say ‘Long live the Shah’ represents the most complete rejection possible of the Islamic Republic,” Abrams said.

“That doesn’t mean people want a monarchy, even a constitutional monarchy, but he clearly has a support base and might have a role.”

One European diplomat with experience in the region said that Pahlavi may not be a future political leader of Iran but “he represents an idea that captures people’s imagination at a crucial moment.”

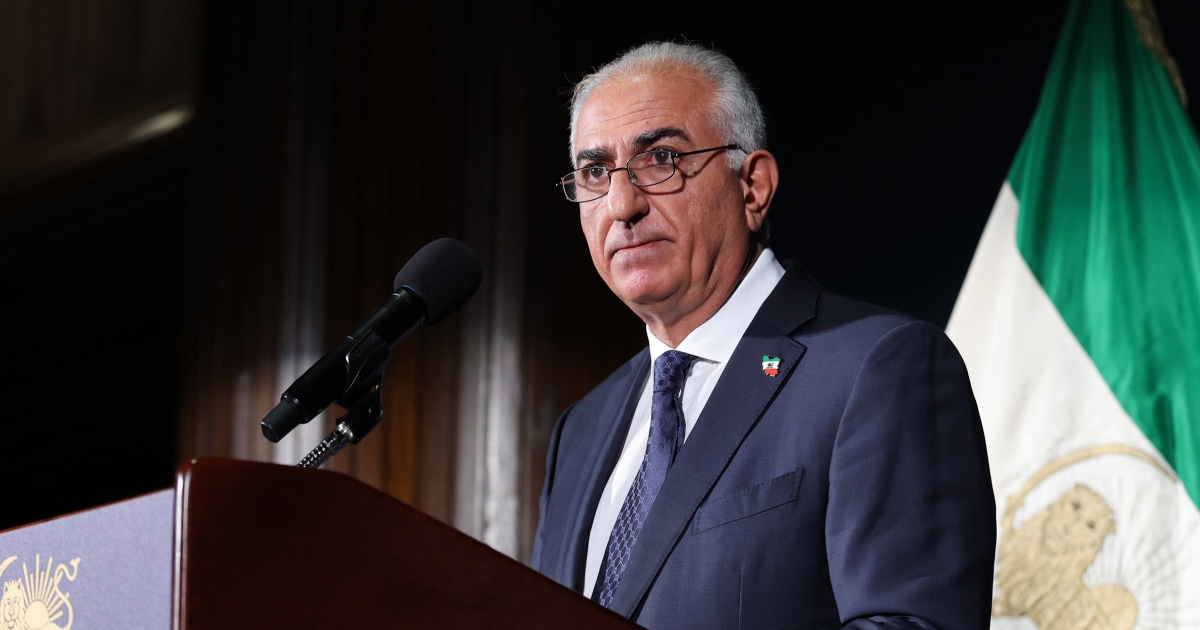

Dressed in a smart blue suit and striped tie, Pahlavi’s appearance before television cameras last week resembled an event for a head of state or a political candidate. He cited a plan he had crafted with experts on how Iran could avoid chaos, revive the economy and move smoothly to a stable democracy.

“My team of experts have developed a plan for the first 100 days after the regime’s collapse and the long-term reconstruction and stabilization of our country,” he said.

The exiled crown prince has proposed to organize opposition to the regime around a short list of universal principles: Iran’s territorial integrity, separation of religion and state, individual liberties and equality of all citizens and the Iranian people’s right to decide a democratic form of government.

Pahlavi, who bears a striking resemblance to his father, says it would be up to Iranians to choose their future government and leaders, and that for the moment he would merely serve as a leader of a democratic transition.

As for the legacy of his father’s rule, Pahlavi prefers not to dwell on the subject, saying, “I’m here to make history, not to write it.”

But some of Pahlavi’s supporters are staunch advocates of restoring an absolute monarchy and have clashed online in harsh tones with those who disagree with their view. That has caused tension among opposition activists, experts say, and could pose a challenge in persuading wavering officials to break away from the regime.

“It inhibits his ability to peel people away from the regime if they feel like … the next rulers of Iran could come after them,” Karim Sadjadpour, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said in an online briefing on Wednesday.

Some opposition activists are wary of forging ties with Pahlavi due to what they say is the fanaticism of some of his followers. But other activists say there is no room for internal feuding at a moment when the regime appears so weak and adrift, and that Pahlavi has to be part of any opposition coalition.

Esfandyar Batmanghelidj, head of the Bourse & Bazaar Foundation, a think tank that studies Iranian politics, said there’s no doubt Pahlavi “is the most recognized leader within the opposition.”

But he said Pahlavi, who has not set foot in Iran since his family was pushed into exile in 1979, lacked a genuine political organization inside Iran “that is able to provide leadership for the protests, not just on social media, but actually at the street level.”

Such an organization would ensure that the protests are disciplined and sustainable over time, Batmanghelidj said.

The way that Pahlavi and other opposition activists have approached the protests “raises questions about their readiness to really lead a political movement.”

He drew a comparison to Maria Corina Machado, the Venezuelan opposition leader who despite years of experience mobilizing resistance to authoritarian rule could not secure President Trump’s support.

“If Machado, with her deep organizing experience, couldn’t win the trust of the Trump administration, how can Pahlavi?”