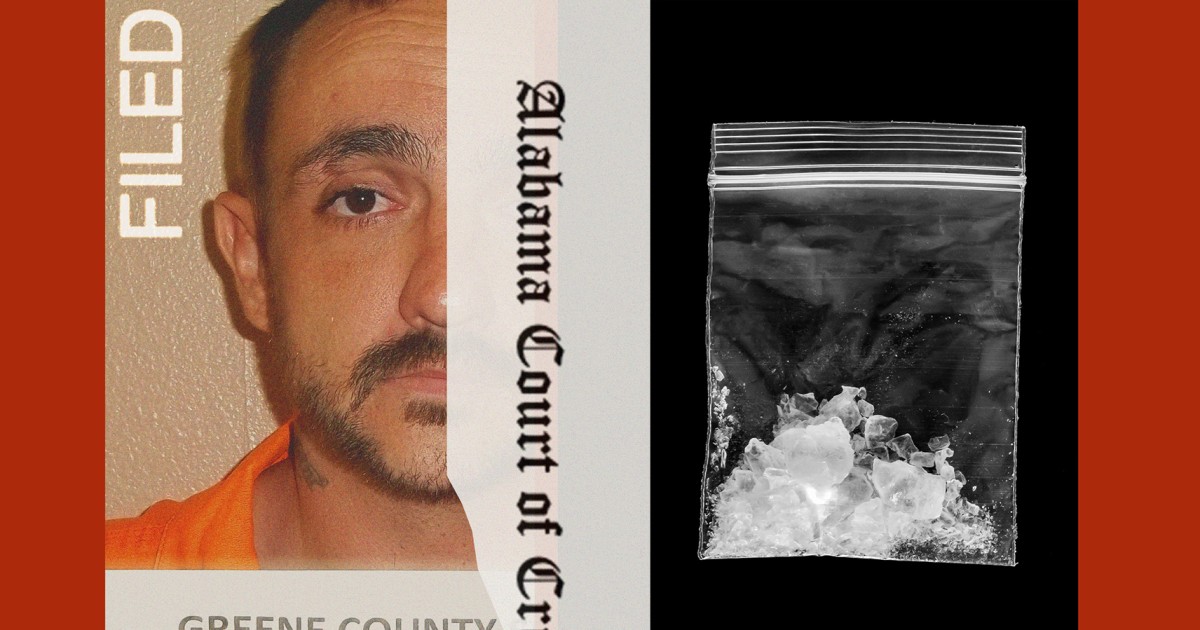

Derrick Dearman appeared to be high on drugs in his Alabama prison in the days leading up to his execution.

The convicted killer raged in phone calls and emails, anguishing over how his willingness to die for his crimes wouldn’t change the perception of him as an irredeemable monster.

And by the time he took his final breath, his longtime addiction to methamphetamine — the drug he blamed for fueling the murders of five people, including a pregnant woman, in 2016 — had consumed him to the end.

Dearman, 36, had meth in his body when Alabama put him to death by lethal injection in October 2024, according to a toxicology report confirming what eyewitnesses believed at the time.

He isn’t the only prisoner to be executed with narcotics in their system in Alabama recently.

Since Alabama resumed executions in 2023, following a pause on capital punishment amid a series of failed lethal injection attempts, the state has executed 11 people, including Dearman. An NBC News review of available autopsies shows that at least three others had taken illegal drugs prior to their executions: Jamie Ray Mills, 50, was executed last year with meth in his body, while Carey Dale Grayson, 50, and Kenneth Smith, 58, died last year with a form of a synthetic cannabinoid in their system, according to their toxicology reports. Synthetic cannabinoids imitate the effects of substances like marijuana.

Alabama has its fourth execution of the year scheduled for Thursday.

Jon Ozmint, a former prosecutor who was the director of the South Carolina Department of Corrections from 2003 to 2011, said that the discovery during autopsy of drugs unrelated to an execution and not prescribed to an inmate would have been “a red flag for us.”

“We definitely would have launched an after-action review, and then, if there was any indication of you know, staff wrongdoing, we would have launched the appropriate level of investigation,” Ozmint said.

Mills was executed by lethal injection, and Grayson and Smith died by an execution method using nitrogen gas. (Smith was the first inmate in the nation to die in that manner.)

The amount of the drugs found in Dearman, Mills, Grayson and Smith was relatively small, independent medical experts who reviewed the inmates’ records told NBC News, but their detection still indicates the drugs had been recently absorbed.

D’Michelle DuPre, a forensic consultant in South Carolina and a former medical examiner, has analyzed about 125 death row inmates’ toxicology reports throughout her career, she said.

“I have rarely seen an opioid in the inmates’ tox screen. I don’t recall seeing a narcotic,” DuPre noted.

Charlotte Morrison, a senior attorney with the Equal Justice Initiative, which represented Mills in his death row case, said drugs are generally less of a problem in Alabama’s William C. Holman Correctional Facility because of heightened security and inmates’ isolation.

However, she said, she’s not surprised to learn that even death row inmates can score drugs, indicating the depths of the problem.

“The entire system is poorly managed,” Morrison said. Drugs “are a pervasive crisis.”

The Alabama Department of Corrections and the state attorney general’s office did not immediately respond to inquiries about the inmates’ toxicology results.

According to the state’s execution protocol, on the afternoon of an execution, “a medical examination of the condemned inmate will be completed, with the results recorded on a Medical Treatment Record or Body Chart.” The Department of Corrections also did not immediately respond when asked if workers are checking for drug use in that final examination and what happens if it is detected.

In a deposition last October involving Grayson’s case, Corrections Commissioner John Hamm acknowledged drugs are circulating in Alabama’s prisons. He agreed that, in some instances, corrections employees may be smuggling the contraband into the prisons and selling them to prisoners.

In recent months, the Department of Corrections said a corrections officer was accused of the large-scale trafficking of narcotics, including meth and marijuana, at the state prison in St. Clair County. Additionally, visitors have attempted to bring drugs into facilities, including at Holman, or used drones to drop backpacks containing drugs onto prison grounds.

The drug trade has had lethal consequences, as well. Of the 277 deaths last year of inmates in state Department of Corrections custody, 46 were classified as “accidental/overdose,” according to an ACLU of Alabama report.

In 2020, the Justice Department sued Alabama for alleged constitutional violations within its prison system, citing instances of excessive force, sexual abuse and poor sanitary conditions. The suit also mentioned the system’s “failure to prevent the introduction of illegal contraband leads to prisoner-on-prisoner violence.”

“The use of illicit substances, including methamphetamines or fentanyl or synthetic cannabinoids, is prevalent in Alabama’s prison for men,” the complaint alleges. “Prisoners using illicit substances often harm others or become indebted to other prisoners.”

The federal government’s lawsuit against Alabama remains ongoing, and the state has largely denied the allegations in court filings.

Carla Crowder, the executive director of Alabama Appleseed, a nonprofit criminal justice reform organization that provides legal and re-entry services, said prison officials have the ability to root out drugs in prisons “from a public corruption perspective.”

“Start tracking down the source — who’s in charge, who’s calling the shots,” Crowder said. “We are advocating for the state to begin to take this seriously.”

During Commissioner Hamm’s deposition, one of Grayson’s lawyers pointed out the ability for some death row inmates to acquire drugs, including his own client — and questioned whether that affected Grayson’s ability to meaningfully participate in his own defense.

“Mr. Grayson admitted that he was on drugs at the time of his deposition or had taken them in the immediate — in the preceding 12 hours,” lawyer Spencer Hahn told U.S. District Judge R. Austin Huffaker Jr.

“I don’t understand how a person who is being held on single block at the most secure prison in the state of Alabama is allowed to alter his consciousness using drugs before a deposition that is central to his case,” Hahn said. “So a lot of what Mr. Grayson said and may not have said, he was not in his right mind in a lot of ways.”

Hahn added that Grayson had been under the influence of flakka, a synthetic stimulant similar to the more commonly known bath salts.

He said Grayson’s drug use was also consistent with a synthetic cannabinoid found in Smith’s autopsy. An attorney for the state responded that the synthetic cannabinoid Smith consumed was “smoked.”

Certainly taking drugs is illegal, but so is providing drugs to a prisoner. ”

Said Spencer hahn, a lawyer for a Death row inmate

“Having access to these mind-altering substances can absolutely impact your conscious state and your decision-making,” said David Dadiomov, an assistant professor of clinical pharmacy at the University of Southern California.

Dadiomov also said the way these drugs are used among people who are incarcerated is different because of the setting.

“Things are misused simply based on access,” he said. “At extremely high doses, because these substances are usually very potent, they also cause psychotic-like effects, or effects that are quite different from what people classically view as intoxication from marijuana.”

During Hamm’s deposition, Hahn questioned how Smith could have drugs in his system when he “had been watched for four days straight before an execution.”

“Somehow he was able to, from an isolation cell, obtain flakka or whatever that synthetic cannabinoid source was,” Hahn said of Smith.

“Certainly taking drugs is illegal,” Hahn added, “but so is providing drugs to a prisoner. And somebody got those drugs into that prison.”

During the deposition, the judge suggested drugs could be getting into Alabama prisons another way.

“There has been an issue in the state prison system of lawyers bringing in papers that have been soaked in drugs and then giving them to their clients and DOC, you know, or whatever the facility maybe can’t stop that from happening because it’s legal papers,” Judge Huffaker said. “And then the particular inmate smokes or ingests it or does whatever with it.”

Hahn denied his law office had ever done so.

He declined to comment about Grayson’s case when reached by NBC News this week.

A lawyer for Smith also couldn’t immediately be reached for comment.

Read more death row coverage

Dearman, who initially pleaded not guilty to the crimes, later fired his two court-appointed attorneys and changed his plea to guilty.

In a phone interview with NBC News in April 2024, Dearman said he had dropped the appeals in his case and was ready for the state to execute him on capital murder and kidnapping charges.

Dearman said he was high on meth in 2016 when he burst into a bungalow armed with an ax and firearms in a rural area near Mobile. His estranged ex-girlfriend, Laneta Lester, was staying at the home, which belonged to her brother.

Dearman was convicted of killing five people while they slept: Lester’s brother, Joseph Adam Turner, 26, and his wife, Shannon Melissa Randall, 35; Randall’s brother, Robert Lee Brown, 26; and two others who lived at the home, Justin Kaleb Reed, 23, and his wife, Chelsea Marie Reed, 22, who was five months pregnant. Dearman was also convicted in the death of the Reed’s unborn child.

He told NBC News last year that he was addicted to drugs since he was a teenager and that his dependency on them ignited the rampage.

“Drugs turned me into a very unpredictable, unstable and violent person,” he said. “That’s not who I am. The person that committed these crimes and the person who I truly am is two different people.”

Dadiomov said there is a strong correlation between long-term meth use and severe mental illness, likening meth-induced psychosis to schizophrenia.

“They present similarly,” he said. “They can have the similar features of hallucinations, so seeing things that aren’t there or hearing things that aren’t there.”

Morrison, who represented Mills on Alabama’s death row, said the need for inmates to turn to drugs in prison, and then potentially gain access to narcotics from corrections officers and other employees, only shows the absence of rehabilitation and programming to help prisoners — even those relegated to death row.

“It impacts any sense of hope,” Morrison said. “It’s a system that reflects to an entire group of people that they do not have worth.”